Back to the Trigun Bookclub Archive

Trigun Bookclub By Volume

Trigun: Volume 1 | Volume 2

Trigun Maximum: Volume 1 | Volume 2 | Volume 3 | Volume 4 | Volume 5 | Volume 6 | Volume 7 | Volume 8 | Volume 9 | Volume 10 | Volume 11 | Volume 12 | Volume 13 | Volume 14 | General Commentary

Trigun Bookclub By Member: alena-reblobs | aluvian | annaofaza | anxiety-elemental-kay | caffeinefire | deludedfantasy | discount-kirishima | domfock | dravencore | eilwen | fifthmooon | hashtagcaneven | hikennosabo | iwritenarrativesandstuff | lizkreates | makima-s-most-smile | merylstryfestan | mydetheturk | namijira | needle-noggins | nepentheisms | nihil-ghost | ocelaw | pancake-breakfast | rainbow-pop-arts | retrodaft | revenantghost | sunday-12-25 | the-nysh | weirdcat1213

Original Tumblr Post: Trigun and averting apocalypticism

Trigun Bookclub: Some Very Long-Winded Final Thoughts (for now)

So what’s my takeaway after all this discussion about the allusions to religious concepts and narratives in Trigun? What conclusions does the story draw about faith? And are there any theological ramifications to its message?

From my perspective, the belief system Trigun promotes is a broadly defined humanism that isn’t bound by any religious tradition. Declarations of faith in this story are more often directed at individual people or humanity as a whole than toward a god or metaphysical concept. Trigun says that the purest and most fundamental faith is our belief in one another and in our collective capacity for good, and the specifics of any one person’s faith are worth pursuing so long as it keeps them in the business of living and engaging compassionately with other sentient beings.

In Trigun’s larger thesis on faith, there’s also a notable emphasis on the drive for continued life and hope for a future that can be built in the present world as opposed to glorifying death in the service of grandiose ideals, especially if those ideals center on seeing the world as irredeemable and in need of destruction. And it’s through this message of continued striving in the here and now that I think Trigun brings up its own point of contention against a particular theological perspective. What we have in Trigun is a firm rejection of apocalypticism.

According to the Critical Dictionary of Apocalyptic and Millenarian Movements, apocalypticism is the “belief in the impending or possible destruction of the world itself or physical global catastrophe, and/or the destruction or radical transformation of the existing social, political, or religious order of human society—often referred to as the apocalypse.” In Christianity, this perspective is clearly seen in futurist interpretations of the book of Revelation (the Greek root word for apocalypse – apokalypsis, means revelation or unveiling). This eschatological approach treats the text as a prophetic outline of the end of the world in which God brings judgment through a series of cataclysms and then secures an everlasting paradise for the faithful.

Revelation 21:1-4 (NRSV):

(1) Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth; for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea was no more. (2) And I saw the holy city, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband. (3) And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, “See, the home of God is among mortals. He will dwell with them: they will be his peoples, and God himself will be with them; (4) he will wipe every tear from their eyes. Death will be no more; mourning and crying and pain will be no more, for the first things have passed away.”

As we all know, Knives loves to position himself as a bringer of divine judgment in the same vein as the Abrahamic God.

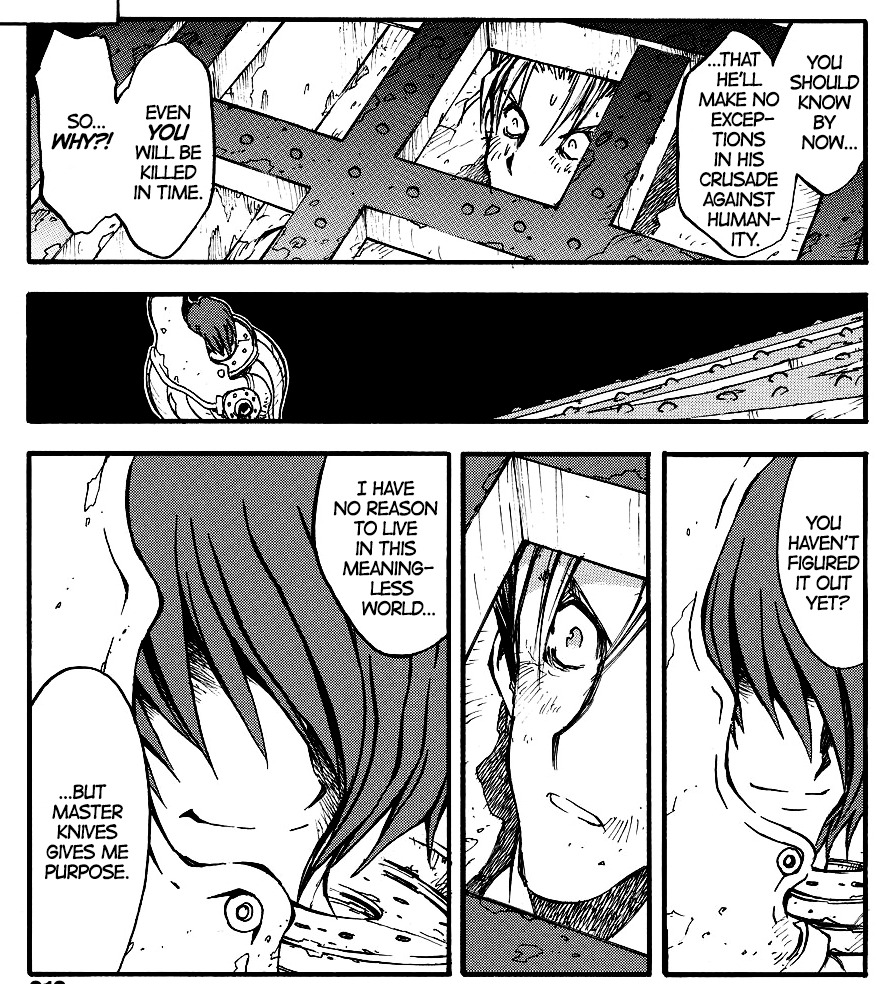

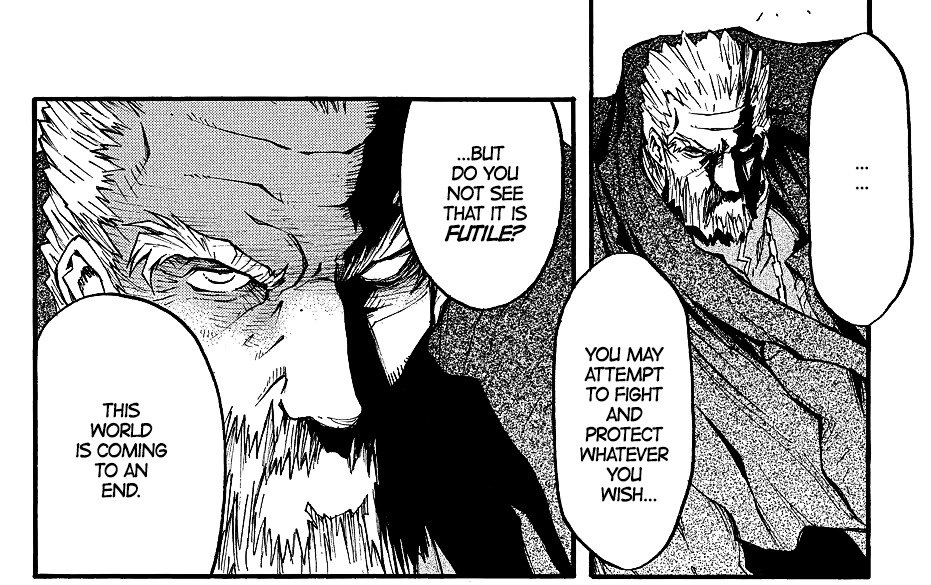

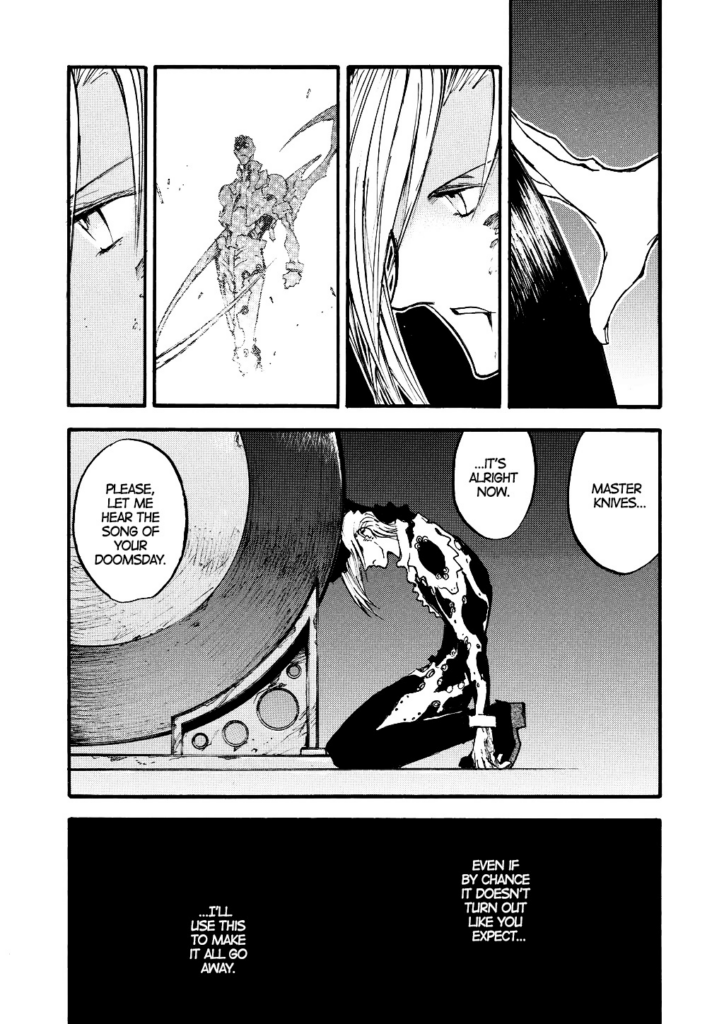

To Knives, humans are a source of evil that have to be purged from his world; salvation for his chosen people (plants – the higher beings) can only come through mass death. The realization of Knives’ apocalypse is doomsday for humankind. No surprise then that in his followers (some of whom revere him like a deity), we see the sentiments of a doomsday cult. To Legato, service to the supreme being is his sole purpose in life; if Knives commands him to die, then he’ll die gladly. For Elendira, the most glorious service to the supreme being is to facilitate his vision for the end of the world, and she wants nothing more than to see it happen. And in Chapel, we see the cruelty and cynicism promoted by the apocalyptic mindset: If the end is inevitable, then all efforts to protect what we have in this world are futile, so what value is there in choosing to be merciful?

The immense harm dealt by real religious groups that hold similar beliefs to these is difficult to overstate. So long as any atrocity in the temporal world can be justified when committed in deference to what are taught to be higher spiritual principles, there are no ethical boundaries these groups won’t transgress. Japanese society in recent history has, in fact, had significant experiences with violent apocalyptic fanaticism. The most well-known of these occurred on March 20, 1995, in which the doomsday cult Aum Shinrikyo carried out its deadly sarin gas attack in the Tokyo Metro subway system. An act of religious terrorism left many dead and thousands injured, all because some people were convinced the world was ending, and it was to their benefit and everyone else’s benefit if they could make it end faster.

The doctrine of Aum Shinrikyo was a mishmash of Hindu, Buddhist, and Christian concepts, and Christian eschatological views on Armageddon were especially influential to cult leader Shoko Asahara’s prophecies in the time leading up to the attack. Common threads in books of the Christian Bible with apocalyptic elements include emphasis on the corrupting nature of the present world and promises of eternal unity with God after a final war in which Christ emerges victorious against all evil. These ideas are also disconcertingly influential in mainstream American Evangelical Protestant Christianity. Even in the most nonviolent Christians who would never dream of associating with extremists, it’s not hard to find an underlying cynicism and detachment with regard to living life in the present. There’s the notion that the world is fundamentally broken and sinful, and believers should look forward to God’s destruction and remaking of it, because perfect happiness can only come in the thereafter.

1 John 2:15-17 (NRSV):

(15) Do not love the world or the things in the world. The love of the Father is not in those who love the world, (16) for all that is in the world—the desire of the flesh, the desire of the eyes, the pride in riches—comes not from the Father but from the world. (17) And the world and its desire are passing away, but those who do the will of God abide forever.

From such a perspective, hope is primarily oriented toward some indefinite point in the future that will come to pass via the eradication of every imperfection that marks the present. What happens in the story of Trigun, however, is an overturning of the apocalyptic narrative. The climax of Trigun Maximum invokes the fantastical imagery of Revelation, creating the impression of a stage set for the definitive final battle between the embodiments of good and evil, but then the story pushes back against the narrative conventions of apocalypticism. There is no end of days, no destruction and re-creation of the world, because it was averted by radical human hope for compassionate understanding in the here and now. And there is no ultimate triumph of Good over Evil in which Satan is cast into the lake of fire. In fact, there may not even be a “Satan” in this story at all.

When Knives collects his sisters into an amalgamated body, his form and theirs take on a draconic appearance, bringing to mind the red dragon of Revelation (that is, Satan). In Knives’ own mind, however, he’s God pouring out his divine wrath on the humans who’ve sinned against him, and there are angelic elements to his design as well to reflect this. Ultimately, his form doesn’t hold. Vash and his human allies manage a breakthrough in communicating with the collective body of dependent plants, and when Knives is cast to the earth (in another departure from Revelation, this doesn’t occur as the outcome of heavenly forces battling against him), he faces Vash one last time as just a man – Vash’s brother who’s lashing out because he never processed his extreme childhood trauma. Because maybe in the end these forces of absolute good and absolute evil don’t exist; maybe our willingness to imagine God and the Devil was always the product of our own messy, conflicted humanity in all its potential for good and evil.

The resolution, then, happens not through one brother killing the other, but through connection and understanding, a little push toward a kinder existence for everyone. Knives ends up having to place his trust in the very humans he hated in order to save his brother’s life, and his faith is rewarded. For Vash and the rest of humanity, life goes on; it goes on in an imperfect present, but it’s a present where there’s plenty of joy to be found nonetheless. So the story closes out under a bright blue sky with the assurance that the song of humanity still sang. There’s no looming threat of doomsday, just a path forward toward more life.